Enormous polygon patterns in rock lie dozens of meters below Mars’ surface, ground-penetrating radar data suggest.

Similar patterns develop on the surface in Earth’s polar regions when icy sediments cool and contract. A comparable process long ago may have created the shapes on Mars, found near the planet’s dry equator, researchers report November 23 in Nature Astronomy.

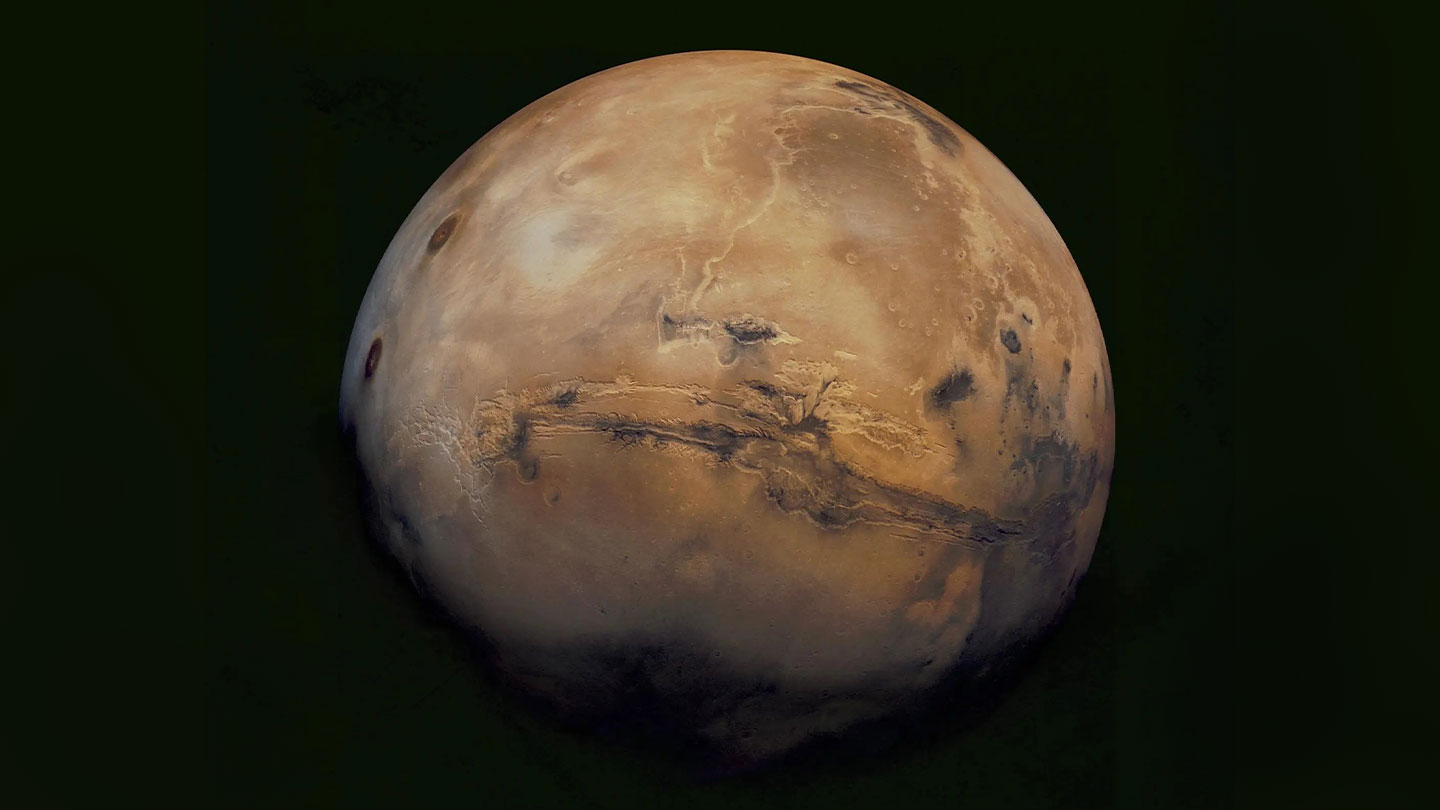

If so, the finding hints that the Red Planet’s equator was much wetter and icier, more like a polar region, when the polygons formed 2 billion to 3 billion years ago.

“Buried possible polygons at that depth have yet to be reported” on Mars, says planetary scientist Richard Soare of Dawson College in Montreal, who was not involved in the study. Searching for ancient polygonal terrain on Mars using ground-penetrating radar is a new idea that “could be powerful,” he adds, and could help scientists understand how Mars’ climate has changed in the past.

On Earth, polygonal terrain forms in chilly climes when sharp temperature drops cause icy ground to contract and crack open. These thermal fractures are small at first. But the little cracks can fill with ice, sand, or a bit of both, forming “wedges” that prevent the cracks from healing and gradually pry open the earth as they grow. Because this wedging process requires multiple cycles of freezing and thawing, polygonal ground is a good hint that the terrain was icy when the patterns formed.

But the Chinese Zhurong rover’s landing site, on a part of Mars called Utopia Planitia, is not the kind of place one would expect to find the terrain on Earth — at least not today (SN: 5/19/21). Polygons have been spotted at higher latitudes on the Martian surface from orbit, but the landing site sits near the Martian equator in a dry, sandy dune field (SN: 8/24/04).

The polygons appear to be roughly 70 meters across and are bordered by wedges nearly 30 meters wide and tens of meters deep — about 10 times as large as typical polygons and wedges on Earth. So it’s possible, Soare says, the structures here formed a bit differently than ice-wedge polygons on Earth.

Forming polygons near the Martian equator wouldn’t be possible today, says study coauthor Ross Mitchell, a geoscientist also at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics. To form polygons, the region must have been colder and wetter in the past, he says — much like a polar region.

Changes in the tilt of Mars’ axis could explain such a shift in climate. Simulations of Mars’ orbit have suggested that the planet’s spin axis has at times been so extremely tilted that the planet essentially lay halfway on its side. This would cause the poles to receive more direct sunlight while equatorial regions froze. Finding potential polygons buried near the Martian equator, Mitchell says, is “smoking gun evidence” supporting the idea that the tilt of Mars’ axis has varied so substantially in the past.

“We think of every planet other than Earth as dead,” Mitchell says. But if Mars’s axis does swing around often, he says, our neighboring planet’s climate would be far more dynamic than currently believed.