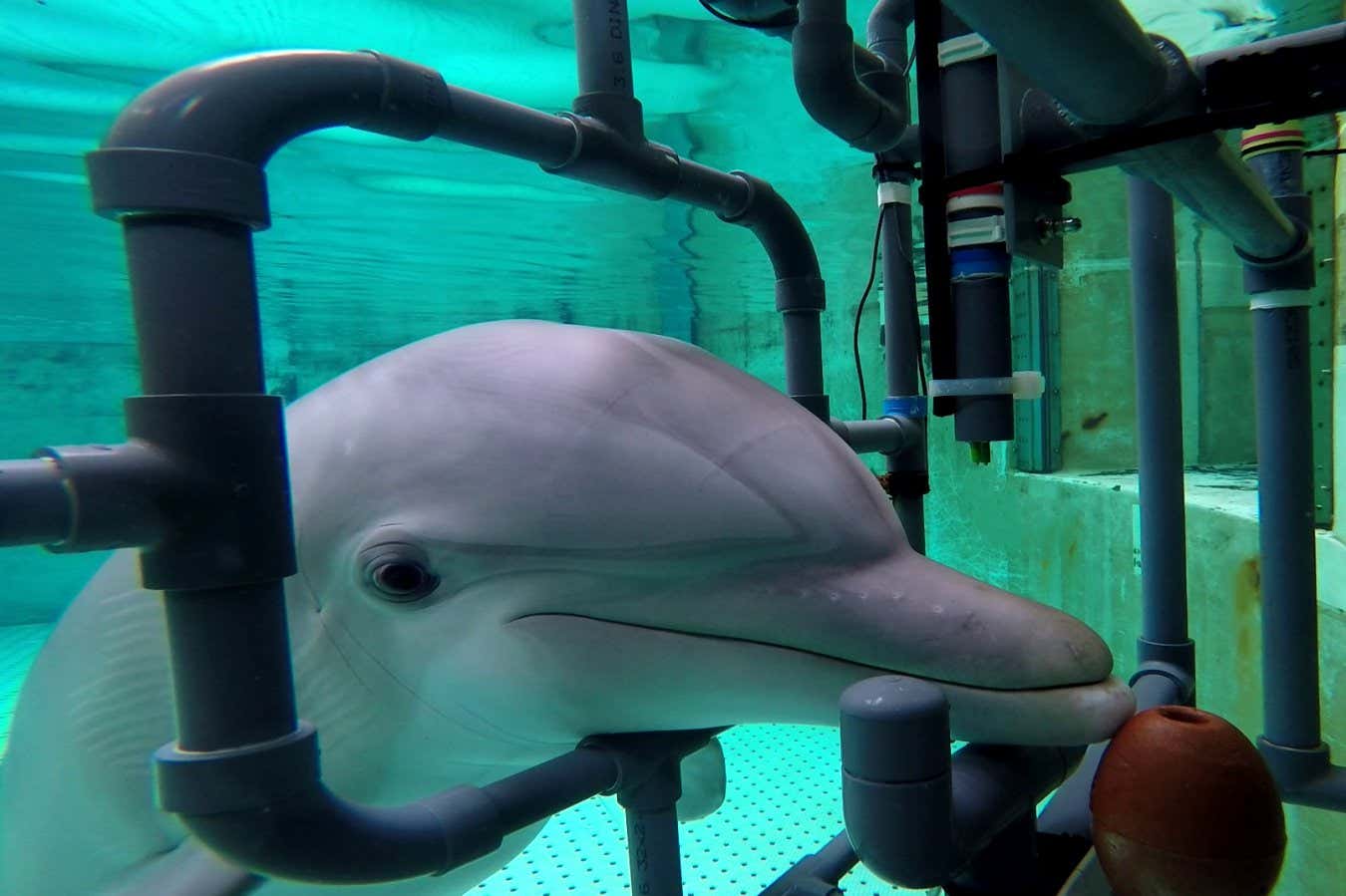

Donna, a bottlenose dolphin, during a test for electricity-sensing abilities

Tim Hüttner, Nuremberg Zoo

Bottlenose dolphins have an extra sense – the ability to feel electric fields – which they may use to navigate and search for food.

The power to sense weak electric fields, known as electroreception, is common among water-dwelling animals, such as sharks, platypuses and rays.

“It’s a pretty old sensory modality,” says Tim Hüttner at the University of Rostock in Germany. “It’s really developed several times across different species.”

Some of these animals generate their own electric signals to sense their surroundings, communicate with others or stun prey.

In 2011, the Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis) became the first marine mammal known to have an electric sense.

Now, Hüttner and his colleagues have found that a second species of dolphin, bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), can also detect electric fields.

Bottlenose dolphins are born with whiskers along their snouts which fall out as they grow up, leaving deep follicles where they used to be.

“It’s like an empty bag in the skin,” says Guido Dehnhardt, also at the University of Rostock. Inside these pits are cells that strongly resemble electric field-detecting receptors that have been found in sharks, he says.

To confirm if they have the power of electroreception, the team decided to put two female bottlenose dolphins at Nuremberg Zoo in Germany, Donna and Dolly, to the test.

In a 12-metre-wide circular pool, each dolphin was trained to rest its head on a metal platform and swim away if it sensed an electric field, which was generated by copper electrodes in the water. If they responded correctly to the stimulus, the dolphins would be rewarded with fish.

Both dolphins excelled at the activity for electric fields as weak as 5.5 microvolts per centimetre.

The team also found that the dolphins reacted to alternating fields, which simulated the pulsating electrical signals that would be given off by fish in nature.

The findings suggest that bottlenose dolphins may well use this sense to hunt for nearby fish, and perhaps even navigate the oceans using Earth’s electric field. But studies of dolphins in the wild are needed to confirm this, says Dehnhardt.

“An exciting direction will be to compare the molecular basis of electroreception across dolphins, bees, platypus, with the slightly more defined properties in fishes to understand evolutionary mechanisms of this incredible sensory ability,” says Nicholas Bellono at Harvard University.

Topics:

- animals/

- whales and dolphins